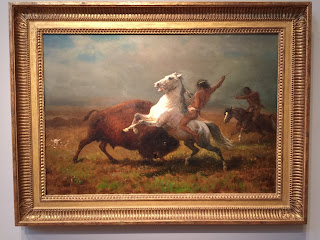

The third painting I intended to look at on my unpresented tour was by Albert Bierstadt, well-known for his majestic pictures of Yosemite (often with Indian villages or groups of Indians situated on the valley floor framed by the enormous granite cliffs on all sides) and for the finished painting "Last of the Buffalo," for which the De Young has a study:

"Last of the Buffalo" captures a moment as if it were a continuing and essential part of the life of the Plains, even as it states by its title that its evocation is, rather, of the notion that the Indians are passing away, like the buffalo, into a gone world. Benjamin Madley in An American Genocide describes how the myth of the inevitable passing of the Indians was used as a way of justifying, sanitizing, and finally forgetting the acts of destruction by invaders that caused that "passing."

The painting I had wanted to look at, "California Spring," has been one of my favorites in the "Hudson River" landscape gallery of the De Young for many years, and I've frequently looked at it on other docent tours for its pastoral peacefulness, its situation in a part of the Sacramento Delta that can be visited less than an hour away from San Francisco, its tiny thumbnail of the state capitol building on the horizon, and the magnificent weather effects of the storm in the middle distance, backlit by the emerging sun.

But now there's another resonance in the painting for me: the realization that this European-style pastoral landscape can only exist because of the active destruction of the Indian-shaped landscape (and its sources of all that was needed to support the lives of the local Indians for thousands of years perhaps), first by the Spanish and Californio pastoralists who brought herds of cattle to the state, and then by the more systematic genocidal policies of the Californian and U.S. governments and their gold-hungry invading co-conspirators.